It is almost redundant here to write a thesis about certain figures in history but is history more than dates? Yes, history is more than dates, names, places and events even though these are necessary but the ultimate goal here is to discover how they lived and thought. It is about how they interacted with others that makes history fun and interesting instead of tedious and boring. Unfortunately, because, we know so little of their lives with the exception of their tombs that we can only piece together slivers of their lives. In the final instalment of the series here, it is endeavoured to give an account of the life of the second-to-last king of the IV dynasty, Menkaure, who built the last pyramid on the Giza plateau and discuss the economy of the Old Kingdom whilst leaving the art and architecture of the Old Kingdom for the next entry.

|

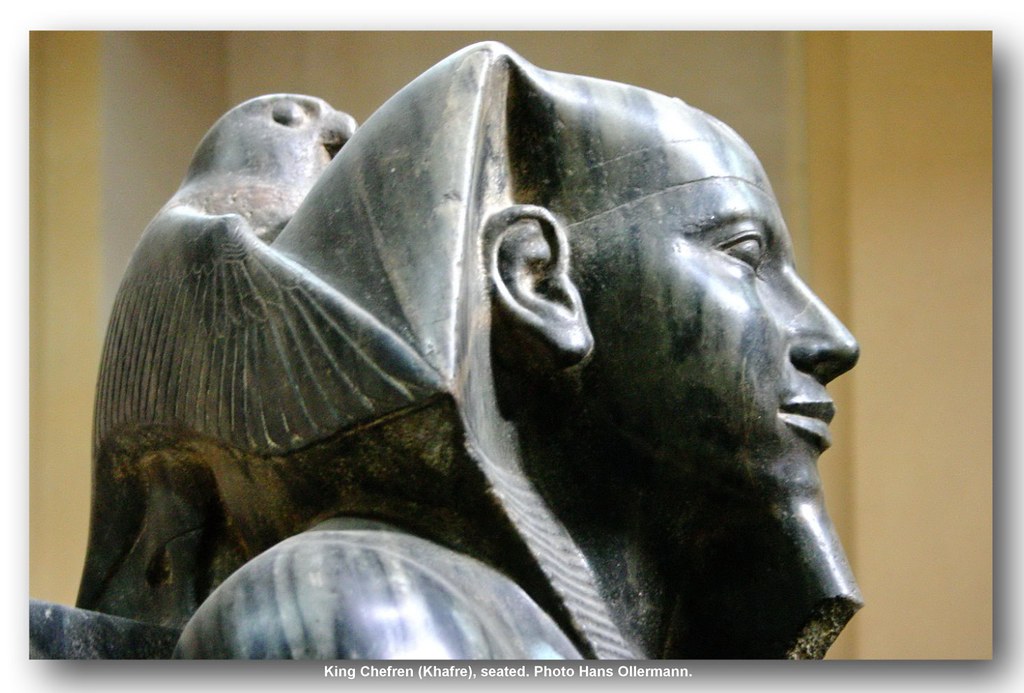

| Head of Menkaure made of Alabaster |

The son of Khafre and possibly Khamerernebty I, Menkaure, whose name means Eternal like the Souls of Re, was the final king to build his pyramid on the Giza plateau. He built his pyramid mostly of granite which is more prestigious than limestone with which the prior kings constructed their enormous pyramids albeit it is at a smaller height because of its cost. Menkaure, unfortunately, was not even able to complete his tomb which was left to his successor, Shepseskaf, the last king of the IV dynasty who strangely abandoned the idea of the pyramid for an oddly shaped sarcophogal tomb. The reason why escapes Egyptologists (Shaw, 2000). Menkaure may have also had three wives, two of which we know, Khamerernebty II and Khentkawes I, the latter of whom we know does have a tomb located in Abusir.

| Pyramid of Menkaure |

Why was Menkaure's pyramid the last of the great pyramids though? Yes, there were many more pyramids to come but they were smaller in comparison. Most did not exceed 60 metres (200 ft), (Wilkinson, 2013). The answer lies in the economy. According to Ian Shaw of Liverpool University, the large construction carried out during the 3rd and 4th dynasties had a profound effect not only on the economy but Egyptian society as well. One can imagine the amount of professional workers needed to construct such colossal tombs involving the construction of the pyramids and transport of Egypt's resources. It forced the re-allocation of the workforce during the inundation to work on the pyramids but return to the floodplains when the inundation receded. Because such a large workforce was needed, it increased the demand for greater agricultural production which did strain or pressure the Egyptian economy. (Shaw, 2000).

| Menkaure probably with his wife courtesy of arthistory resources |

All of this in turn, allowed for greater organisation throughout Egypt. Once again Ian Shaw explains why. The already existing administrative centres throughout Egypt became the capitals of their respective nomes. We saw in a previous entry that Den, of the 1st dynasty, removed whole communities and labelled them, "crown land" in order to consolidate the country thereby increasing the power of the king, himself and creating the nomes themselves (Tippett, 2015).This seems to be a major reorganization since Pharaoh Den of the 1st dynasty. At this time in Egypt, the pharaoh had unrivalled power. Menkaure was able to commandeer people and land as well as tax the populace at will. Members of the royal family held administrative offices as well in the 3rd and 4th dynasties. The idea of nepotism seemed to work extremely well in these dynasties, especially without the concept of money, until the construction of these elaborate tombs. This allowed for newcomers, who were not related to the king but were literate and competent, to enter into positions previously forbidden by the king. These new officials were rewarded with estates and land ex officio thereby weakening the power of the king which would come in play later in the Old Kingdom, particularly in the 6th dynasty when the power of the kings was so weak that it allowed for nomarchs (governors of nomes) to rebel. This paved the way for private ownership and wealth.

In conclusion, Menkaure was the last pharaoh to build his pyramid on the Giza plateau albeit at a smaller height given that he built it mostly out of granite. Although he reigned roughly 28 years, he is credited with creation of private wealth and ownership that saw unrelated, literate people be given administrative offices as a reward for their service to the king, ex officio. This was however to be the end of the Age of the Pyramids and no more would we see construction on such a scale as this throughout Egyptian history. It certainly was a monumental achievement that forever branded Egypt as the land of the Pyramids.

Page Break

References

Shaw, Ian. 2000. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.

Wilkinson, Toby. 2013. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt.

Tippett, Adam. 2015. Horus Who Strikes.

http://barqueofthenile.blogspot.com/2015/06/horus-who-strikes.html